Daniel Barcelos Vargas*

From COP21 held in Paris in 2015, all countries of the world have committed to setting their own emission reduction targets, according to their capability and criteria. The means of ordering a new appointment was the call. NDC , Nationally Determined Contribution,

Countries adopted different approaches to demarcate their commitments thus opening a new chapter of tension in climate governance. Starting with a comparison of national commitments. As countries use different parameters in their NDCs, it is not always clear or simple to translate ambition and outcomes interchangeably.

Some countries set absolute targets: Brazil, the European Union and the United States, for example, pledged to reduce annual greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. Brazil has promised to reduce emissions by 50% compared to 2005. The EU, 55% compared to 1990. and the US, between 50–52% compared to 2005.

Other countries chose targets related to GDP. For example, China has committed to emitting 65% less carbon per unit of GDP in 2030 than in 2005. In return, Indians set a target of 33-35% less emissions over the same period.

Notably, GDP-intensity NDCs—such as in China and India—are a simple system that links emissions reductions to economic growth. In other words, the criterion for measuring progress in climate commitments is gains in energy efficiency relative to GDP.

The target enforces that the carbon-GDP ratio should fall. But if GDP grows, as is expected in the Chinese economy, then the absolute balance of national emissions should also increase, without violating climate commitments to the world.

Each country still has the autonomy to define its own national emissions inventory methodology. That is to say, the “measurement” of how much each country emits is based on the parameters set by the country itself. For example, Thailand does not consider emissions from land use change in its calculations. Brazil, yes.

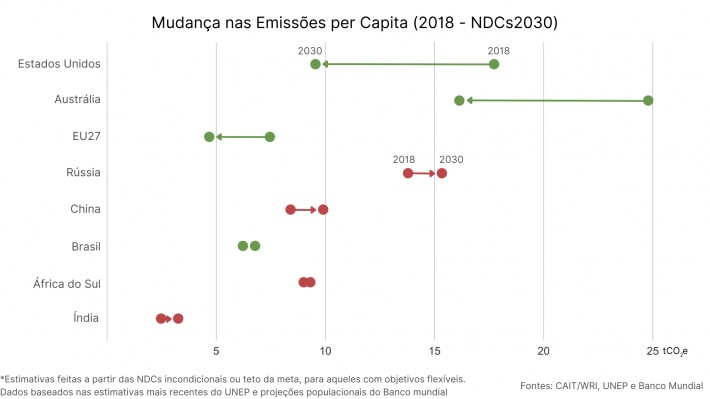

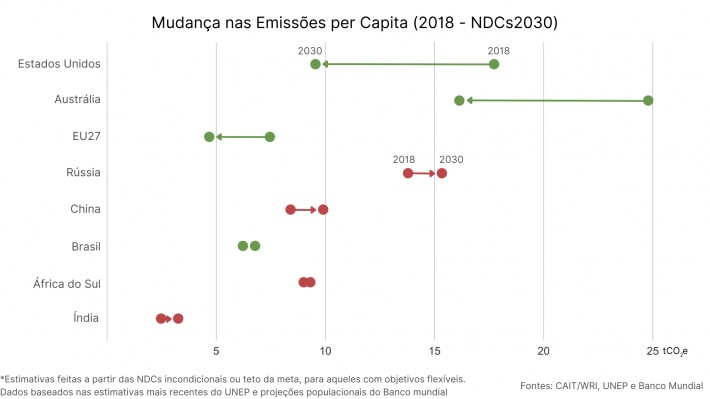

Finally, variations in NDC arrangements and calculations hide huge disparities between countries and parts of the world. Compare Australia to China. On the one hand, Australia has set a clearly bold target to cut emissions, as seen in the chart below. China, in turn, expects emissions to increase by 2030. Even if both meet their NDCs, Australia will maintain per capita emissions much higher than China.

The contrast with India is even more symbolic. The country has relatively clear goals—and opposes a rapid expansion in its commitments. However, India’s per capita emissions today are much lower than most countries in the world. For example, a US citizen emits 9 times more carbon than an Indian. Even if the United States drastically reduces its emissions over the next few years, the US carbon footprint will remain many times larger.

COP26 took the first step towards harmonizing “language” among NDCs and, in doing so, facilitated comparison and transparency in relations between countries. In the coming years, however, we are likely to see significant discussions about how to reconcile the different methodological parameters and, in particular, how to ensure the fair distribution of the decarbonization burden among countries with very different degrees of development.

*Professor at FGV EESP and Coordinator of the Observatorio da Bioeconomia at FGV.