On to Charlotte!

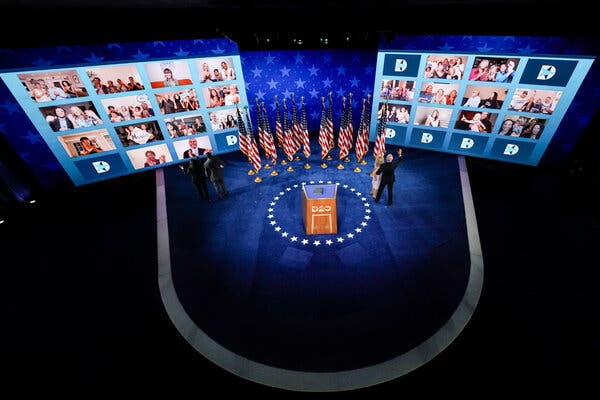

OK, not really. But with the Democrats’ virtual convention behind us, and drawing generally strong reviews, attention is turning to what the Republicans might do with their time in the spotlight, which starts on Monday.

In some ways, having the Democrats go first was good for President Trump’s party. Democrats got to take the virtual car out on a test ride and, presumably, the Republican National Committee got some good ideas for their own convention. And it’s always better to go second and have the last word. On the other hand, the bar has been set fairly high by the Democrats.

Here’s a list of things we’ll be looking for when the Republican convention is gaveled to order:

-

Will this be an all Trump, all the time convention? Joseph R. Biden Jr. appeared each night from Delaware, doing panels with small groups of people, but he listened more than he spoke, until it was time to give his acceptance speech. Will Mr. Trump be as yielding of the spotlight?

-

Democrats sketched a rich and sympathetic portrait of their candidate, walking viewers through the formative tragedies of his life. Next week should provide a test of whether that dissuades Mr. Trump from going after Mr. Biden. And if Mr. Biden gets a bit of a pass, will Senator Kamala Harris, Mr. Biden’s running mate, become the lightning rod?

-

How much attention will be paid to the pandemic? Mr. Trump’s campaign has already dismissed the Democratic convention as grim and gloomy, with its focus on the devastation being wrought by the coronavirus. Will Republicans offer a more optimistic vision of how the nation is managing the virus, or push the issue into a corner?

-

Will Republicans be as diligent about wearing masks and social distancing as Democrats were through the week? Or will they be deliberately and conspicuously more lax, making a political statement as well as a health one?

-

Will Mr. Trump use this platform to lay out a second-term agenda? Democrats are betting he will not. “He’s not going to change,” said Rahm Emanuel, who was White House chief of staff when Mr. Biden was vice president. “He’s not going to offer an inclusionary, second-term agenda.”

-

Will Mr. Trump (and, for that matter, Vice President Mike Pence) allow this convention to promote the next generation of potential presidential candidates? And will we see as many non-politicians — a.k.a. regular Americans — in prime spots as we saw at the Democratic convention?

-

Will there be a lineup of Hollywood stars to give the convention more celebrity power? Will the Republicans have the kind of musical production numbers to counter the Democrats, who offered performances by, among others, John Legend and Jennifer Hudson? (Ronna McDaniel, the R.N.C. chairwoman, told us this week that the convention would shun Hollywood celebrities in favor of “real people.”)

-

The speaking roster at the Democratic convention had a heavy representation every night of people of color and women. Will this be a priority for Republicans as well?

-

Democrats put the virtual campaign to good use, turning to imaginative and highly produced videos to showcase voters and party leaders, and for such convention fixtures as the keynote and the roll call. Will Republican convention planners do the same, or stick with the old script?

The Biden granddaughters were lovely. Shorter speeches were effective. The travelogue roll call made for strangely good TV.

Those were concessions that Trump advisers and former White House officials had to hand to the Democratic National Committee after it pulled off the first-ever virtual convention, even while they took issue with the overall message of the week.

The question is, how do they top that now? It may be difficult.

Republican officials wasted time that could have been used to plan a highly produced semi-virtual convention by trying — for much longer than the Democrats — to pull off a normal one. President Trump scrapped his plans for an in-person convention in Jacksonville, Fla., just a month before the event itself was scheduled to take place.

Instead of handing over the reins to an experienced television producer, Mr. Trump is trying to weigh in on much of the programming himself, mostly with the help of people from his own White House. And he’s insistent on having it still look on television like a “real convention,” i.e., with an audience component, and on playing a major role himself every night.

The D.N.C.’s four nights showcasing the diversity of the Democratic Party also heightens the pressure on the Republican National Committee and Mr. Trump to do more than appeal to aggrieved white voters. Republican officials are planning to highlight Mark and Patricia McCloskey, the white couple from St. Louis who brandished weapons at Black Lives Matter protesters in June. Will the convention have a message for people other than the president’s hard-core base?

A national political convention gives presidential candidates their first major opportunity of the campaign to connect with a national audience, reaching viewers by the millions and kicking off the race’s climactic final leg.

Until recently, it also usually meant the candidate would get a bump in the polls — like a guaranteed $200 for passing “Go” — though bravura performances tended to add a few extra points to the so-called convention bounce.

The average convention bounce has been on the wane in recent years — and with the coronavirus limiting the convention’s proceedings, this could be the year when the bounce disappears completely.

Of course, we probably won’t have enough polling results until next week to measure the effects of the Democratic National Convention, and we’ll have to wait longer to determine the impact of the Republican convention, which begins Monday. And, historically, convention bounces have mostly tended to wash out anyway: Both parties are about evenly likely to get a bump, and voters’ preferences tend to revert within a few weeks, or to be swayed in a fresh direction by newer developments.

Still, the fact that the campaign bounce itself is on the wane carries implications about the state of play in politics more generally.

American politics have grown more deeply partisan over the past few decades, so there’s far less fluctuation in pre-election polling. Put simply, persuadable voters are in short supply.

I’ve attended every convention since 1988, when Michael J. Dukakis accepted the Democratic presidential nomination. That year, as I exited Atlanta’s rapidly emptying Omni Coliseum after the balloons had dropped, I stopped to chat with a prominent Southern Democratic senator. He was all smiles, sure that the party’s four days of festivities would lead to Mr. Dukakis beating George H.W. Bush. Like thousands of other Democrats in attendance, he thought it was in the bag.

They were wrong, of course, and Mr. Bush triumphed. But that was one of the beauties of conventions — the visceral feel of politics, the coming together of thousands of people devoted to American political life and perhaps witnessing something that might only bear fruit years later. And, of course, there were the over-the-top parties, private concerts, battles for credentials and bleary-eyed early breakfasts following essential late-night intelligence gathering.

This year, I’m not bumping into anyone to receive immediate if flawed analysis as I watch the scripted and occasionally prerecorded speeches on C-SPAN from my pandemic bunker.

Many are saying that the virtual convention is the way of the future, and none other than Joseph R. Biden Jr. suggested Tuesday that the old ways are done. That would be too bad, because the much-ridiculed conventions served many purposes.

A lot of business got done at them, and many indelible images of convention spontaneity remained long after the circus had departed Houston or San Diego, Chicago or Tampa.

“I loved every moment of it,” said Terry McAuliffe, the former Virginia governor, national party chair and convention chair. “I usually got two or three hours of sleep,” he said. “It was a great reunion.”

And convention life extended far beyond the arena stage. Campaign operatives must be crying over the lost fund-raising opportunities. The conventions presented a glorious display of wretched excess, the Washington swamp at its soggiest, with endless wining, dining and schmoozing.

Viewers this year got to hear from Democratic officials and ordinary voters without the powerful cheering and chanting from the convention floor. But think about how important the roar of the crowd was for a barely known U.S. Senate candidate from Illinois during his 2004 keynote address.

“I don’t believe the Obama speech would have had the same impact virtually,” said David Axelrod, Barack Obama’s campaign adviser at the time, adding that “you do lose the kinetic connection between the speaker and the crowd.”

Whether you liked the content of Joseph R. Biden’s Jr.’s acceptance speech Thursday night at the Democratic National Convention or found yourself unmoved by his message, one thing was clear: He outperformed the low expectations set in part by the Trump campaign.

It’s not the first time the Trump campaign has botched the expectations game, and outside advisers have tried to warn the president that he needs to raise expectations of his opponents, rather than lower them, while lowering expectations for himself.

But that hasn’t stopped the president from bragging to people that he expects a matchup against Mr. Biden on the debate stage to be a bruising experience for his opponent.

Mr. Trump was eager to run as an underdog four years ago, but this time the campaign has sought to project an image of dominance, in ways that are not always helpful.

In Tulsa, Okla., Brad Parscale, Mr. Trump’s former campaign manager, violated a cardinal rule of politics: Underestimate crowd size and enthusiasm in order to over-deliver. Instead, he made the president look foolish when only 6,300 people showed up for an event he claimed had drawn 1 million ticket requests.

Instead of talking up how Mr. Biden could be a formidable opponent on the debate stage, Mr. Trump and his campaign advisers have mostly done the opposite. Donald Trump Jr., the president’s eldest son, claimed recently that there was “an active push to get Joe Biden to not debate my father” because of concerns that he was not capable of handling the matchup.

Jason Miller, a campaign strategist, has tried to shift how the campaign is framing Mr. Biden and the debates. “Joe Biden is actually a very good debater,” he told The Washington Post. But after all that came before it, the lone comment from one operative did little to really raise the bar.

George H.W. Bush was in trouble. It was July 1988 and Michael Dukakis, the Democratic candidate for president, was on a roll after his party’s convention in New York. A Gallup poll showed Mr. Bush trailing by 17 points.

But he had a road map to victory.

One month earlier, Mr. Bush’s top aides had gathered to review a thick binder of polling and focus group data, finding that Mr. Dukakis’s record was not well-known and that some of his liberal positions, in particular supporting prison furloughs and opposing the death penalty, could swamp him in a general election.

The Bush campaign proceeded, as Lee Atwater, the campaign manager, put it, “to strip the bark off the little bastard,” beginning in force with Mr. Bush’s hammer of a speech at the Republican National Convention.

Mr. Bush not only overcame Mr. Dukakis’ summer polling advantage, but defeated him handily: by a margin of 53 percent to 46 percent.

In many ways, the Bush campaign of 1988 marked the birth of the modern-day negative campaign. Most memorably, Republicans plastered Mr. Dukakis, then the governor of Massachusetts, with the case of Willie Horton, an African-American man who raped a white Maryland woman and stabbed her boyfriend while on a Massachusetts prison furlough program.

As President Trump faces similarly daunting poll deficits in his contest with Joseph R. Biden Jr., he is increasingly running one of the harshest campaigns since 1988, and Republicans preparing for their convention next week are looking back at that race as a beacon of hope in a bleak political landscape.

Mr. Trump and his political and media allies have torn into Mr. Biden and particularly his running mate, Senator Kamala Harris, using racist and sexist attacks. There is a direct line between the hard-edge campaign Mr. Bush ran portraying Mr. Dukakis as a far-left liberal — and the racial undertones personified by seizing on Mr. Horton — and the Trump campaign that is emerging today.

“The problem for Trump is he has yet to find his Willie Horton, as it were,” said Susan Estrich, who was Mr. Dukakis’s campaign manager. “But he’s looking.”