After months of work, the UK has ditched the way its coronavirus-tracing app works, prompting a blame game between the government and two of the world’s biggest tech firms. So what went wrong?

At the end of March, I got a text from a senior figure in the UK’s technology industry. This person said they were helping the NHS “on a very substantial project that will launch in days and potentially save hundreds of thousands of British lives.”

That was the first I knew of the plan to build a contact tracing app, a project that soon appeared to be at the very centre of the government’s strategy to beat coronavirus and help us all emerge from lockdown.

The tech luminary had somehow assumed that I could be an adviser to the project – I made it clear that could not be my role but I was very interested in following its progress.

Now, nearly three months on, after missing deadline after deadline, there has been a radical change in direction. The app that has been developed so far is being scrapped, and a new approach will be tried based on a system created by Apple and Google.

But there is no guarantee when, if ever, this will be rolled out. So what went wrong?

March

When the team from the NHSX digital division was assembled they were told they were engaged on a vital mission. According to a presentation the team was shown the Covid-19 app would have four aims:

- Stop or slow the epidemic

- Control the flow of patients into hospitals

- Help people return to normal life

- Gather secondary data for use by the NHS and strategic leaders

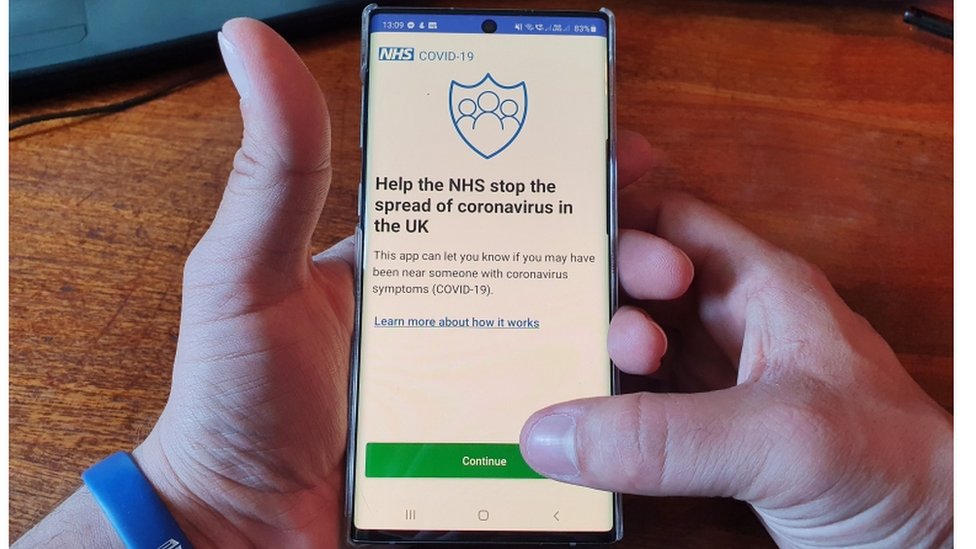

Once installed on a user’s phone, the app would use Bluetooth to keep a record of other people with whom they came into close contact – as long as they too had installed the app. Then when someone tested positive for the virus, alerts would be sent to their close contacts of recent days telling them to go into quarantine.

The epidemiological expertise was provided by a team of Oxford scientists who had argued that there was an urgent need to identify people who were spreading the virus without knowing. “Very fast contact tracing was likely to be essential,” says one of the Oxford team, Dr David Bonsall. “And smartphones have the technological capability to speed up that process.”

But using the Bluetooth connection on smartphones to detect contacts was untested technology. Still, the team was inspired by Singapore, which had released its Trace Together app using that system.

April

But it soon became clear that using Bluetooth was tricky. Reports from Singapore suggested people were reluctant to download the app because it had to be kept open on the phone all the time, draining the battery.

Then on 10 April came a surprising announcement from Google and Apple. The two tech giants – on whose software virtually all the world’s smartphones depend – said they were going to develop a system that would help Bluetooth contact-tracing apps work smoothly. But there was a catch – only privacy-focused apps would be allowed to use the platform.

Apple and Google favoured decentralised apps, where the matching between infected people and their list of contacts happened between their phones. The alternative was for the matching to be done on a central computer, owned by a health authority, which would end up storing lots of very sensitive information.

The app the NHS was developing was based on a centralised model, which the Oxford scientists felt was vital if the health service was to be able to monitor virus outbreaks properly.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Two days later, with quite a fanfare, Health Secretary Matt Hancock unveiled the plans for the Covid-19 app, promising “all data will be handled according to the highest ethical and security standards, and would only be used for NHS care and research”.

But immediately privacy campaigners, politicians and technology experts raised concerns. “I recognise the overwhelming force of the public health arguments for a centralised system, but I also have 25 years’ experience of the NHS being incompetent at developing systems and repeatedly breaking their privacy promises,” said Cambridge University’s Prof Ross Anderson.

Yet the project was still gathering pace with the first trial of the app at RAF Leeming, in Yorkshire. The trial was held under artificial conditions, with servicemen and women placing phones adjacent to each other on tables to see what happened.

Meanwhile, privacy-conscious Germany became the latest country to switch its app to the decentralised model, using the Apple and Google system. It seemed that Apple had made it clear that it would not cooperate with a centralised app.

Michael Veale, a British academic working with a consortium developing decentralised apps, warned that the NHS app was on the wrong path, asking on Twitter “will the UK push ahead with an app that will not work on iPhones – which has devastated adoption in Singapore?”

May

Media playback is unsupported on your device

But the UK pushed ahead with a trial in the Isle of Wight. As it got underway Mr Hancock told the public they had a “duty” to download the app when it became available and that it would be crucial in getting “our liberty back” as the lockdown was eased.

First sight of the app showed it was very simple, asking users whether they had a fever or a continuous cough. But any symptom alerts sent out to contacts merely echoed the standard “stay alert” advice – test results couldn’t be entered into the app at this stage. It left many residents confused.

Still, the fact that the app was quickly downloaded by more than half of the island’s smartphone users saw the government branding the trial a success.

Meanwhile, the Financial Times revealed that the government had hired a Swiss software developer to build a second app, using the Apple and Google technology. NHS insiders were quick to downplay the significance of this move – although one admitted “Downing Street is getting nervous”.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Work continued on a second, more sophisticated version of the original app, which was again going to be tested in the Isle of Wight before a national rollout – though the original deadline of mid-May had been missed.

On 20 May, however, it became clear that the government’s focus was switching to manual-contact tracing. The prime minister announced that a “world beating” tracing system would be in place by the beginning of June, though Number 10 stressed that the app’s contribution to the system would come a bit later.

As May drew to a close the boss of the wider test and trace programme, Baroness Dido Harding, said the app would be the “cherry on the cake” of the project. It was no longer the cake itself.

June

By early June, more deadlines for the national release of the app had come and gone. Three weeks into the Isle of Wight trial residents were getting restless, with very little information on how it was going or when an updated version of the app was coming.

France launched its centralised Stop-Covid app, which had drawn heavy criticism from privacy campaigners, and digital minister Cedric O said 600,000 downloads in the first few hours was “a good start”.

On 4 June, Business Minister Nadhim Zadhawi was coaxed into saying the app should be ready by the end of the month, but that was the last firm deadline that would be promised.

Singapore, which had continued to struggle to make its contact tracing app work, announced plans to give all citizens a wearable device in the hope that this would do a better job than a smartphone.

On 14 June, Germany became the biggest country to launch a decentralised app on the Apple/Google platform. It quickly outstripped France in terms of downloads with something approaching 10% of the population installing it.

By now the silence from the UK government about the NHS app was deafening. What was going on?

Around lunchtime on 18 June all became clear. The BBC broke the story that the government was abandoning the centralised app and moving to something based on Google and Apple’s technology. Despite all the spin, the Isle of Wight trial had highlighted a disastrous flaw in the app – it failed to detect 96% of contacts with Apple iPhones.

The blame game has already begun. Mr Hancock and some of the scientists working with the NHS believe Apple should have been more cooperative. Technology experts and privacy campaigners say they warned months ago how this story would end.

Apple says it did not know the UK was working on a “hybrid” version of the NHS coronavirus contact-tracing app using tech it developed with Google.

Meanwhile, there is scant proof from anywhere around the world that smartphone apps using Bluetooth are an effective method of contact tracing. Back in March, it seemed that the hugely powerful devices most of us carry with us might help us emerge from this health crisis. Now it looks as though a human being on the end of a phone is a far better option.