Dominic Hirsch. Photo: Disclosure

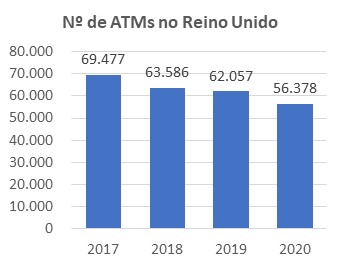

The number of ATMs in the UK declined by more than 13,000 (19%) over the three-year period, from the end of 2017 to the end of 2020, and is expected to fall further this year. The media is full of reports of an increasing number of “cash deserts” – geographic areas where the public has to travel long distances to get cash because ATMs, bank branches and post offices have been closed or removed.

But how did this situation happen, and have there been lessons learned that can be applied in Brazil?

Over three quarters of ATMs in the UK are free to use, and for these machines, the ATM owner receives an interchange fee, known as an interchange fee, paid by the card issuer, for each cash withdrawal. In mid-2018, and again in early 2019, the UK interchange fee was reduced, the first and second of four planned 5% reductions in interchange fees. The timing could not have been worse as it coincides with the growth of electronic payments and the decline in the use of cash, and while these interchange fee reductions may seem small, the profit margins on UK interchange fees are low and that of combination transactions. Declining numbers and low revenue per transaction meant that many ATMs were no longer viable. Some ATM owners have tried to convert their free ATMs to pay-to-use, usually charging GBP 2 (14 reais) directly to the consumer for cash withdrawals, but this allows cash in these machines and most ATMs. The number of withdrawals has further decreased. This means that they were not yet durable.

LINK, which operates the UK’s national network of ATMs, canceled the third and fourth interchange fee deductions that were planned, meaning the current cash withdrawal interchange fee in the UK is GBP 0 for a branch ATM. .23 (1.7 reais) and GBP 0.26 (1.9 reais) for external machine. Based on its strengths, LINK has also launched a number of initiatives to help address the situation, including rewards on standard interchange fees at selected locations and the ability of local communities to apply for ATMs at selected locations to improve financial inclusion. is included.

Despite these changes, the UK government remains concerned about the social effects of less access to money. It has already introduced legislation this year to help address the problem, allowing customers to withdraw cash from retailers without making a purchase, and is currently consulting on proposals that may be applied to major financial institutions. Set minimum access to cash rules that apply. .

An important lesson from this recent history of ATMs in the UK is that ATM deployment is extremely sensitive to fee levels, and small fee changes can have unintended consequences if ATM owners cannot cover their costs. The situation is further exacerbated in an environment of contactless mobile payments and increased usage of payment cards.

Through their system of four free cash withdrawals per month, the Brazilian and UK ATM markets are similar in that most cash withdrawals are free for customers. Since the charges are paid by the card issuer to the ATM owner, the issuing banks are committed to ensure that these charges are as low as possible. To some extent it is efficient, as fares are set too high, risk of over-provisioning, but interchange fees are relatively low in both Brazil and the UK by international comparisons. The UK experience shows us that the risk is much greater in the other direction, leading to the unplanned creation of a ‘hard cash desert’.

*Dominic Hirsch, Executive Director of RBR