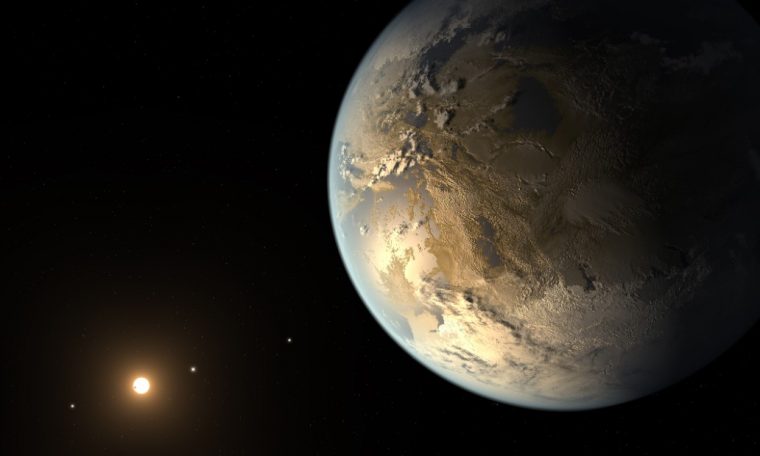

And just as scientists are searching for other planets outside our solar system, called exoplanets, which can host life, Earth-like planets cannot be far north.

In the new study, Schulz-Makuch and colleagues identified 24 exoplanets and exoplanet candidates (planets that have not been positively confirmed). All of these are 100 light-years away, which could be a claim to pleasant planets with favorable living conditions above Earth.

However, the authors caution that this does not mean that they have confirmed that life exists on these planets. Instead, it means that there may be planetary conditions that are conducive to life.

“We warn that when we search for superhuman planets, it does not necessarily mean that they have life (or complex life),” said Schulz-Makkuch. “A planet can be livable or pleasant but faith can remain. It has to do with the planet’s natural history. There could have been a disaster (like a nearby supernova explosion).”

Schulz-Makuch identifies a beautiful planet as “any planet that has more biomass and biodiversity than our current Earth.” It must be a little bigger, bigger, hotter and wetter than the earth, he said.

“The habitation of our planet has also changed throughout our natural history,” he said. “For example, the Earth with all the swamps and rainforests in the Carboniferous Time Period (which produced most of our current gas and oil) was probably unnatural – using our definition – more so than the current Earth. “

Longevity stars

One of the factors of superhubility could actually be the type of star in the planetary cycle. Researchers have identified the dwarf star as the most ideal in the study. These stars have a longer lifespan than our Sun, so life is likely to be sustained and flourish on the planets in the orbit around them.

The dwarf stars are cooler, less massive and even less bright than us Sun, but they can last from 20 billion to 70 billion years. The planets orbiting these stars will be much older and will allow time for life to reach the complexities that come with coming to Earth.

The Earth is about 4.5 billion years old. But in the study, researchers suggest that five to eight billion years is actually a “sweet place” for life to form and evolve.

Our sun is less than 10 billion years old, and it took about four billion years before any kind of complex life could develop on Earth. Stars similar to our Sun could actually die before complex life planets could orbit them.

Other criteria were used to determine superhighty out of 4,500 known exoplanets.

The planets were probably Earth-like, or Earth-like rocks, orbiting in the habitable zone of their star – the distance from the star where liquid water could remain stationary on the surface of the exoplanet.

They looked at size and mass and estimated that 1.5 times the Earth’s mass would be able to maintain internal heating for the Earth and have a greater robustness that would keep it in its atmosphere longer.

A large amount of water on a warm planet, about 8 degrees Fahrenheit above Earth, may also be suitable for life. The study authors compared this preference for warmth and humidity to the biodiversity of the earth’s warmer trees – especially when compared to areas that are colder and drier.

Of these criteria, Schulz-Makkuch thinks that the most important thing for the planet is to host a star, and for Earth to be slightly larger than Earth.

Although a planet may be superhable and meet only a few criteria without checking all the boxes, the authors warn that there is a lot more information that cannot be assessed about the planets.

Schulz-Makuch warned that, like most of the Earth’s deserts, “a slightly higher temperature could make things worse.”

Looking for a pleasant world

It is located in the ocean about 3,000 light-years from Earth. This star is 77% of our Sun’s radius and 76% of its mass, with 34% of our Sun’s light. And this star is about 5.5 billion years old, or a billion years older than our Sun.

The authors provide a small portion of the report card for the star that revolves around the study based on what they know, which they believe is not too much.

“The point is that these candidates should be selected to be potentially livable or superhable, and they should be given priority for further investigation,” Schulz-Makuch said. “In addition, we need to better understand how the planet is made habitable and how biology interacts with its natural environment.”

But in order to fully evaluate these candidates, Schulz-Makkuch sees the need for probes or landings on the planet – but they are all far away, unlikely. However, better remote observations with future space telescopes may help to focus more on the details of these planets.

“It’s sometimes difficult to explain this theory of beautiful planets because we think we have the best planet,” said Schulz-Makkuch. “We have a lot of complex and diverse lifestyles, and many that can live in very high environments. It’s good to live a harmonious life, but that doesn’t mean we have the best.”

Astronomers and planetary scientists Sara Sagar see the study as “a great resource for everyone to use as a reference”. Sieger, a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, was also not involved in the study.

“It’s a great description of all the content for a habitable world,” Siger said in an email to CNN. “I like the idea of superhubble exoplanets. The concept is a good one, oh Olympic athletes like us humans.”

And Caesar agrees with what the authors say as a result of their paper.

“Observations of livable or pure livable exoplanets are still so challenging that nature will ultimately determine what targets we can use with our next-generation binoculars,” Seeger said.

“This is followed to see if the planet is actually habitable. If there is water vapor in its atmosphere (an indicator of surface water on a rocky planet), then measure the potential of the planet and Search for biological gases.

“So while the sample list of exoplanets is quite long, none are within 100 light-years. There is no suitable device for observing with our next generation binoculars. ”